I promised an update on spreading the gospel of daily reflection to my pre-calculus students. It’s coming. In the meantime, I felt like an honest state-of-the-teacher report was more in line with the tenor I’d like to set on this blog. A note: I wrote this two weeks ago because I was looking to meet my self-challenge of one post per week. The tone was a little negative, though. I’m not against putting negative thoughts out into the universe, but I try to avoid it, especially if the negativity relates to something very fixable, something like lack of sleep, poor discipline, excessive festivity, etc.

Long story short: I let it sit for two weeks with the promise to check back and post if it still held up.

The title of this entry, for those unfamiliar, is a term borrowed from the world of technology, specifically the culture of software programming.

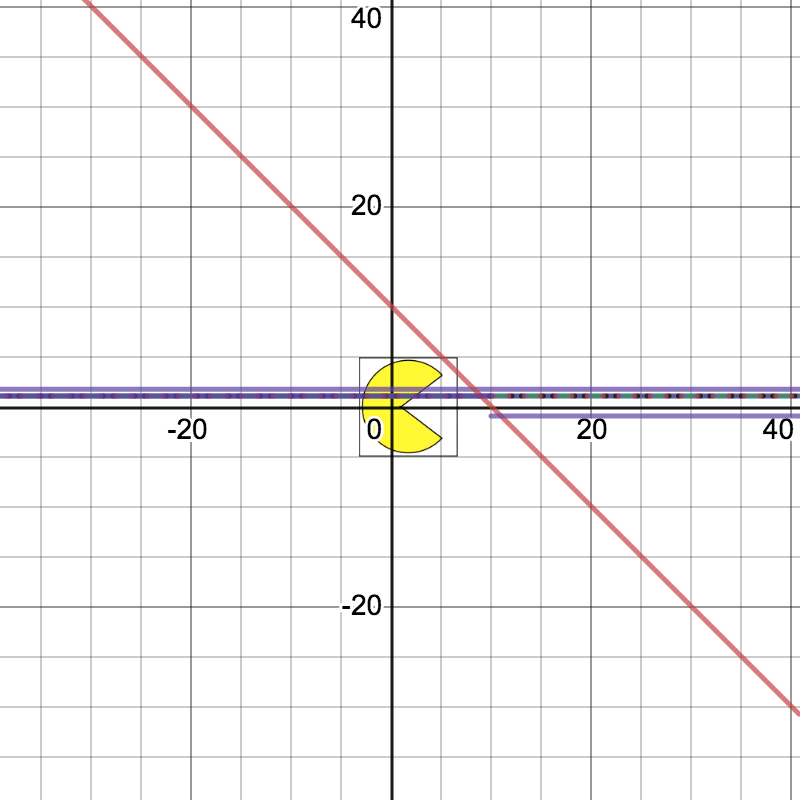

“Yak shaving” is how programmers describe the absurd set of roadblocks that can often pop up whenever you need technology to work properly before you can solve a technology problem.

A typical Yak shaving scenario runs something like this: You want to follow the advice of a friend and install a productivity app, something they say has made their work a million times easier. You start by searching for the app (10-20 minutes), trying to installing said app (10-20 minutes) only to find out your phone won’t connect to or cooperate with the App Store. Some online research (10-30 minutes) confirms that updating your iOS might solve the problem, meaning another download (10 minutes) plus restarting the phone (5 minutes) plus a half-dozen user agreements (10 minutes), maybe even a password reset (5 minutes) and a two-factor verification (5 minutes). Sure enough, once you get the app working, you notice that other apps suddenly appear non-responsive.

Add it all up and what started as an attempt to gain a few minutes of efficiency has now blossomed into an emergency trip to the Genius Bar and a weekend’s worth of lost personal time.

That’s pretty much what the first two weeks of the 2021-2022 school year felt like to this teacher.

For me, the fairly simple task was getting my returning seniors to restart their journals and getting my new seniors in Pre-Calc to launch their own journals..

In the case of the returning students, the plan was to simply say “Ladies, gentlemen and non-binary members of the classroom community, please restart your journals.” In the case of the newcomers, my strategy was to put a journal template on Google Classroom and use the “make a copy for each student” feature to guarantee a fresh crop of journals.

Students are experts at finding the flaws in any well-architected lesson plan, so I knew I’d hit some snags. What I didn’t take into account, or didn’t fully take into account, was the fact that our school had picked Sept. 13 as the date to migrate all Google-based files from a school domain to a schools.nyc.gov domain and how this would throw a never ending sting of monkey wrenches into the start-of-year plan.

Monkey wrench #1 was the fact that each student would have to get used to using a new email address to access Google Classroom. Monkey wrench #2 was that the old, school domain address (essentially Gmail) was suddenly dead, meaning that students who had access to their journals on Friday, suddenly found themselves blocked from updating or, in some cases, finding any of their previously saved work from the prior school year.

A few students came up with clever work arounds — sharing document ownership to non-school accounts, for example — but getting this information to flow through a 125 student cohort was a painful game of “Listen up.” By the end of the first week, a full 20 percent of my students had yet to wake up to the new email address mandate and were doing the classic teenage strategy of laying low and waiting for the teacher to drop a zero grade on their first journal check before asking for help.

And then there was me: Logging into Google Drive under my old user name only to find files I’d written, titled and saved just five minutes before utterly absent. Like one of Dr. Pavlov’s dogs, , I eventually learned to read the resulting adrenaline spike as a cue to get over my own stubbornness and start busting the new DOE log-in, which now sends me to a secondary screen and for reasons I still have yet to fully fathom, a weird alternate reality version of Drive, where everything I’ve saved over the last seven years still exists but shows up in reverse order of importance or timeliness.

By the end of the first week, I was worked. By end of the second, I was fully pissed. Every day seemed to deliver a new snag: No wi-fi on Tuesday, meant no quick fixes at the start and end of class. On Wednesday, a cloned “Journals” folder that appeared empty every time I opened it, suddenly turned out to have all my students’ work when I put it into the trash (to avoid the distraction of me clicking on an empty folder titled “Journals,” mind). I rescued the folder after the fifth student complained about someone putting their work in the trash. On Thursday, however, I was still cleaning up the mess, replacing links to documents titled “John Doe TOK 2021-2022 Reflections” with links titled “Copy of John Doe TOK 2021-2022 Reflections” or in some cases “Copy of Copy of John Doe TOK 2021-2022 Reflections.

On Friday, I pulled a similar bonehead move. For some reason, probably me not following instructions during the server transfer, I had a cloned set of folders, completely empty, showing up as the top pick whenever I did a Drive search. I eventually bundled them all into a “Dead Drive” folder and tossed it in the trash only to find out that, to Google’s internal search engine, they were quite living and somehow connected to all the files I was now learning to access through my “Live Drive” folder.

I’ll be honest. I experience a bad yak shaving adventure at least once a year. It’s just my nature. I ignore software updates. I make do with blown amps and tangled wiring systems. I’m slow to take the car in for regular tune-ups. Eventually, it all builds up to a breaking point and, sure enough, at the exact time I need things to work, like the start or end of a school year, Murphy’s Law kicks in.

Even worse, I knew things were building up over the summer. My main laptop, a MacBook that had kept me running and multi-tasking through the depths of remote instruction, was already starting to do the Apple product death spiral when I accidentally dropped it in July. Suddenly, the keys at the center of the keyboard no longer worked, making it impossible to even log in.

Strung out between per session (overtime) and the other supplemental pay windfalls a New York City teacher comes to rely upon for tech expenditures and holiday gifts, I went the cheap route: I bought a $20 outboard keyboard on Amazon and resolved to upgrade to a new laptop in August. When August rolled around, however, my intercessory prayers to Steve Jobs delivered a rare Apple miracle: My laptop keys came back to life, working on a fairly reliable basis assuming I rebooted the computer and gave it a few minutes to warm up.

It wasn’t until I was finally back in the building that giving my computer a few minutes to warm up each time I switched a power source stopped being a viable option. Come Yom Kippur, our only Jewish holiday respite in New York this fall, I atoned for my sins, dusted off the Visa card and drove over to Best Buy to get myself a new laptop.

Two weeks ago, I predicted that I might look back on this entry and roll my eyes. In some ways I do. Polishing up this reflection for publication, I’ve elected to edit out a two paragraph rant about Hurricane Ida which, though only a tropical storm when it reached New York City, delivered Gulf Coast rainfall numbers to the tri-state. Compared to those who actually suffered through the same weather event, my family’s story is pretty trivial. It bears noting, however, that, consistent with the prior passage, a stitch in time (or, in my case, a routine sump pump inspection) might have saved nine.

Now that I do look back, though, I see some elements of frustration that still merit attention. Like: Why did my school (or school district) choose what was already setting up to be a chaotic and emotionally-fraying period for teachers and students alike as the exact time to migrate to a new server platform? I’m sure there’s an official reason having to do with security, streamlining and federal mandates about student data, but one of the leading reasons I and so many colleagues embraced Google Education platform when it first hit our school in 2014 was because of the relative openness and ease of use. Instead of logging into some crusty old nyc.boe.net server and getting pressed to make a password update, we could simply click on gmail and have the intended addressee’s name autocomplete after the second key stroke.

I realize the road to software hell is paved with user interface shortcuts, but as a veteran teacher, I can smell the machinery of bureaucratic control revving up after 18 months of relative inactivity. Just as it now takes a mask, a positive health screening and, come Monday, a record of at least one vaccination, to enter a New York City school building, it now takes two log-ins, a browser profile check and a daily trip through the Outlook haystack to keep up with things that, three months before, came to me.

As I’ve resolved to keep a more orderly set of folders and filenames, I can already feel the stress of mid-September fade. The ghost files and cloned folders are slowly moving from the top to the bottom of each new Google Drive search, provided I remember to follow the steps noted above. That is, when the Internet chooses to cooperate. I’m finishing this polish after a two day service outage that, according to rumor, affected every school building across theborough with nary a news story or even an apologetic internal memo.

In short, My yak, though freshly shaved, is already at the five o’clock shadow stage.